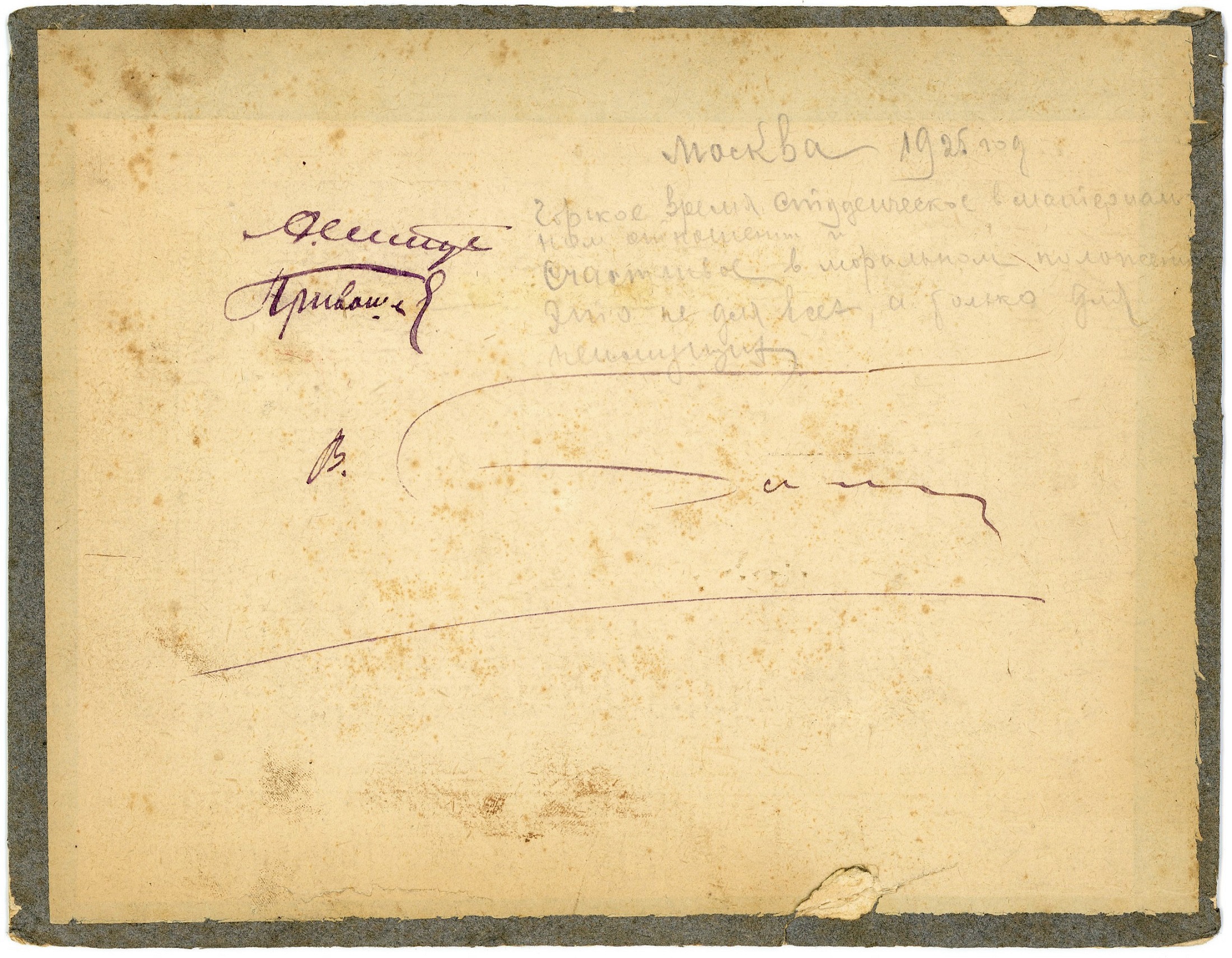

The back of this photograph is signed in ink. Part of the name looks like Arivash, but I can’t read the rest. There’s also an inscription in pencil which is legible.

The inscription:

Москва 1925 год. Горькое время студенческое в материальном отношении и счастливое в моральном положении. Это не для всех, а только для неимущих.

Moscow 1925. A hard time for students materially and a happy time morally. This is not for everyone, but only for the poor.

When the writer says, “This is not for everyone, but only for the poor,” I assume he or she means that the hospital served only the poorest residents of the city. Another possibility is that “the poor” refers to the medical workers themselves, who probably received little pay for long hours of work. Some of them may even have come from humble backgrounds. The reference to students may indicate that this was a teaching hospital or one where medical students were required to work.

The photograph was taken only eight years after the Soviet government withdrew from the First World War in 1917, and just two years after the Russian Civil War ended in 1923. Much of the country lay in ruins. According to Wikipedia, “Disease had reached pandemic proportions, with 3,000,000 dying of typhus in 1920 alone.” Further, “By 1922 there were at least 7,000,000 street children in Russia as a result of nearly ten years of devastation from World War I and the Civil War.”

I’ve divided the photo into two parts, below. Some of the faces look tired or careworn. How much suffering had they witnessed? Were they optimistic about the future? The inscription suggests that the writer found meaning in the work, despite the ongoing hardships.

If you’re curious about economic conditions in the USSR in the 1920s, this article about the New Economic Policy (NEP) provides a good introduction.

7 million street children simply boggles the mind.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, the statistics are staggering. Conditions improved after 1923, but only until 1928, when Stalin came to power. Thanks for your comment, Shayne.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Some of the eyes seem to hold secrets.

LikeLiked by 4 people

No doubt! I can’t imagine the things they might have seen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing faces in that!

LikeLiked by 1 person

and the chap left in the front row is a soldier, wonder if he’s a patient or a guard?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very good question. My guess would be that he was in charge of security. He looks tough.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The statistics are frightening and terribly sad. The hospital workers were so devoted to helping in such an impossible situation.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, and I think that’s something they’d have in common with medical professionals today–a determination to help, regardless of politics.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m remembering reading in Doctor Zhivago about the conditions that led to the appalling poverty and disease in Russia during that time period. One woman on the right in the first photo is looking shellshocked.

LikeLiked by 5 people

You’re the second person to mention Doctor Zhivago in a comment under one of my posts. I remember it as a very visual book, very descriptive. Have you ever read Isaac Babel? Some of his stories are set in the same time period. He was a great Russian Jewish writer who isn’t so well-known in the West.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, I’ve read a few of Isaac Babel’s short stories–although it was a very long time ago.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Same here. I wrote a term paper about Red Cavalry for a Russian lit class in college. It wasn’t light reading, but it made an impression.

LikeLike

Their eyes. Some are almost blank stares.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, they look exhausted. Like many hospital workers over the past year.

LikeLike

They’re all so somber. That may have been the style of the time in photography, but given your background info, also the trials they faced as hospital workers.

I’m intrigued by the woman in the front wearing a doctor’s white coat and a tie (front row, center, of the second crop). It appears only one other woman is similarly attired (but it’s hard to tell), so I’m wondering if she was a trailblazer, a doctor in a time when women were rarely allowed that status.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a great question, Rebecca. By 1925 the Soviet government may already have been promoting women in professional roles–for ideological reasons and also practical ones. I suspect few women had opportunities to become doctors in Imperial Russia, but I’ve never looked into it. The woman you mention is definitely one of the more intriguing people in the photo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s always amazing where do you find such unique photographs? I think the issue of poverty applies to students and young doctors.I know about attraction of new students to educational institutions – children of workers and poor peasants. (a reform of medical education was carried out). Learning has become an opportunity for everyone. But, studying to be a doctor is long, and the scholarship, as you know, does not allow to lead a luxurious lifestyle. Maybe they are interns of a large hospital and somewhere among them there are future excellent doctors who saved dozens of people.I really like this photo. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You know, when I first read the inscription, I also thought “неимущиe” referred to the medical workers. But I couldn’t figure out how that would be true. Your comment has helped me understand! I’ll add that alternative interpretation to the text of the post.

There are many photo dealers now in Russia who sell on eBay. I buy from one in St. Petersburg. This photo came from her. I can send you a link to her listings. Thank you for your very helpful comment!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am pleased to help you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not a lot of happy going on in that photo. Those were some pretty grim stats.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I could have included more grim stats, but then the post would have been too depressing. Thanks for reading, Eilene!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t help thinking about all these people, once children, who of course must have had dreams and thoughts about the future, but were caught in so much hardship, surrounded by different wars. This photo seems to catch them in a relatively “calm” period, but maybe hope was no longer a strong companion in their lives…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder if they grieved the Old Russia that was gone forever, or if they believed in the new regime and its egalitarian goals. Depending on how much they lost–family, friends, property, status–they must have felt conflicted at the very least. Did they choose to stay in their homeland, or did they have no choice? Thank you for your very thoughtful comment, Thérèse!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, so much to think about when looking at this photo, seeing all these faces. Many of them probably never got the chance to decide their own destiny. Like so many others trying to survive where conflict has become all too present.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The clothing seems to point to quite a mix of people: medical, military, volunteers of no particular background. That makes sense to me, because there would have been a need for workers of all sorts. When I was working at the hospital in Liberia, that was the way it was. If there was a job that needed doing, the point was to do it, regardless of credentials, training, and so on. Highly educated people occasionally took on the most menial tasks, and those with no education at all rose to every sort of occasion. A strange combination of exhaustion, pride, and determination usually emerges, as I’m sure it did in the Russia of this time.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I wondered about the people in the photo who aren’t wearing white coats. Some are dressed like administrators–wearing ties, for example–while others are wearing dark outfits that look more utilitarian. Your interpretation of the scene, based on your own experience, makes a lot of sense. Great comments, Linda!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a thought provoking photograph, Brad. I notice that several people themselves have sores or scars on their faces. The expressions on most of their faces are very much those of war torn areas.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree, Mary Jo. We don’t hear much about hospital workers suffering from PTSD, but how could they not? We hear words like strained and exhausted, but there must be longer-lasting effects as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow…they look like they’ve seen things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The faces of the people depicted in this photo express various emotions, but the ones that attract the most attention are those that clearly show fear, depression and suffering.

These people have something to compare with. They lived and worked in tsarist Russia and felt the power of the Bolshevik dictatorship very well. They witnessed all the stages of the development of this young, cruel and inhumane emerging system.

Famine, wounded Red Army soldiers from poor strata of the population, violence, rudeness and humiliation, typhus, plague, smallpox, “Spanish fever”, cholera, malaria, constant control of the Chekists, dependence on the decisions of illiterate people. With every year of strengthening and developing the power of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the hopes of returning to the old system are being dashed among people who were born and brought up in the Russian culture of the pre-revolutionary period.

Every day they are under extreme stress and fear for their lives. These medical professionals are very well aware of the statistics of the dead and the causes of deaths. Such statistics were deliberately underestimated by the ruling dictatorship and strictly controlled to avoid disclosure.

The workers’ collectives were infiltrated or recruited by individuals who wrote denunciations of certain statements, including dissatisfaction with the authorities. Decent people with noble origins were forced to survive, they did not have the same resourcefulness and ability to adapt as the poor.

People from the poor class, on the contrary, felt too comfortable under this power, in this environment. The “proletariat” had the priority right to enter universities, the opportunity to receive free education. It seems to me that the author of the letter meant exactly this, addressing the addressee with sad irony and regret. He took a great risk by writing such a letter on the back of the photo.

Brad, thank you so much for what you’re doing. I admire you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your very thoughtful and enlightening comments, Elena. As you suggest, educated professionals were often treated disdainfully by the new regime, or were viewed as hostile to the new order. Medical knowledge would not have protected them from harassment or repression by the Bolsheviks, despite the grave need for their skills. They would have worked in a climate of constant fear and intimidation. And yet, many continued to do their work to the best of their ability. Their actions were based on moral principles, professional pride, and a genuine desire to help their fellow men and women. Some may have felt a patriotic duty, regardless of the regime in power. These individuals deserve to be remembered for their dedication and their many sacrifices.

Thank you again, Elena. Your comments are always very much appreciated!

LikeLike

Great post. What an inspiration.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike